Insite was Canada’s first supervised injection site. Its 2003 opening was a harm reduction victory but didn’t lead to badly needed solutions to save lives.

Article content

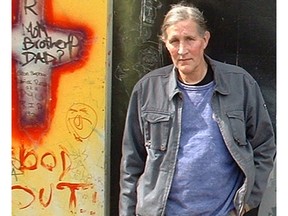

Longtime drug-user Dean Wilson was one of many advocates who fought to open North America’s first supervised injection site in Vancouver 20 years ago. They were an eclectic group that included former drug-users, community activists, a conservative mayor and middle-class parents of addicted children.

Following a years-long legal and moral battle, the contentious facility prepared to open its doors on Sunday, Sept. 21, 2003, on East Hastings Street, the epicentre of Vancouver’s HIV and heroin-overdose crisis. Wilson recalls sitting that day in the “chill room” with Mark Townsend, co-founder of the non-profit group that fought hard for Insite.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Article content

“Do you want to be the first to use it?” Wilson remembers Townsend asking him.

“Well, of course I do. Are you crazy? I spent my whole life on this — well, the last three years of my life,” he responded.

With that speedball — a hit of heroin and cocaine — Wilson became the first of thousands of people to use Insite, the first place on the continent that had the blessing of governments and health officials to supervise people using drugs and, crucially, provide assistance if they overdosed.

Since the site created a database in 2004, it has counted more than 4.6 million visits, with nearly three million of those using the injection rooms. The key statistic, given the high number of heroin overdoses in the 2000s and the poisoned-drug epidemic in recent years, is this: nearly 12,000 overdoses were reversed by staff.

And zero people have died.

That was why activists fought for Insite, but they’re disheartened by the continual opposition from some politicians and community groups who argue these sites enable drug use rather than focusing on preventing it. This resistance, Wilson argues, has slowed life-saving harm reduction at a time when drug-users are dying in B.C. at a rate of nearly seven a day, and while there has been insufficient public investment in treatment options.

Advertisement 3

Article content

“Thousands of deaths could have been prevented,” said Wilson, who has been clean for 18 months after kicking a 52-year drug habit.

Insite supporters had hoped the groundbreaking facility would pave the way for other supervised injection sites to open in Canada, but, while there are more today, pushback continues in many cities and provinces. And so they continue the fight.

“It was a huge political victory to actually have it open,” said community activist Ann Livingston, who co-founded the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users and was a key proponent for Insite.

“But I just had all of these bruises. It was a tough fight. And I think I realized that every single site in every single neighbourhood of every single city will have to be fought for individually. And that’s certainly what we’re seeing around the world.”

Thomas Kerr, head of the division of social medicine at the University of B.C., was the lead investigator at Insite when it opened and has produced scientific evidence showing it has led to a reduction in deaths, an uptake in treatment and an improvement in public disorder.

“And then there was a substantial increase in the number of supervised injection sites not only in Canada, but internationally. A growing number of countries established these facilities to deal with the challenges of injection drug use, based largely on the data from the Vancouver study,” said Kerr, who is also director of research with the B.C. Centre on Substance Use.

“That felt like a bit of a sweet victory.”

Article content

Advertisement 4

Article content

Drug-users found their voices

But more recently, critics, including Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre, have made accusations about harm reduction measures that are contrary to the scientific data Kerr has collected, he said, which has increased public opposition to these facilities and even caused some to be shuttered.

“It just makes me so frustrated that policymakers ignore the evidence and make decisions based on public complaints because we’re contending with the worst public health crisis in modern history,” said Kerr.

Despite these obstacles, a birthday party was held this week in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside to celebrate Insite and its successes. The B.C. Centre for Disease Control, for example, has modelled data that shows even more people would have died during the poisoned drug crisis if the facility didn’t exist.

And that type of proof is propelling the diverse crew of people who initially fought for Insite to keep championing it today.

“The fact that there haven’t been any deaths (inside Insite) is a truly remarkable success story,” said Tanya Fader, director of housing at the PHS Community Services Society. “It’s certainly one of the proudest things in my life and career that I was able to be a part of getting it open, keeping it open, and having it open to this day.”

Advertisement 5

Article content

Fader was hired by PHS, then named the Portland Hotel Society, in the late 1990s and helped the non-profit’s co-founders, Townsend and his wife Liz Evans, gain community support, lobby officials and fight the backlash against these sites.

In 1998, Fader and other Portland employees organized a remarkable conference in Oppenheimer Park, where they had invited international harm reduction experts to speak. They worried no one would come, but 700 people showed up.

In the same park a year earlier, Livingston and fellow activist Bud Osborn held the inaugural meeting of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU). The higher-than-expected turnout at both meetings signalled the beginning of drug-users finding their own voices to lobby for the services they needed.

Osborn, a poet and former heroin addict who died in 2014, increased his clout by getting appointed as the neighbourhood’s representative on the Vancouver/Richmond Health Board. A charismatic speaker, he also spoke at many local meetings about the need for harm reduction, and how addiction can happen in every facet of society.

Advertisement 6

Article content

“And I know how many places he spoke at because I drove him there — like hundreds of places, usually churches,” said Livingston, who wasn’t a drug-user herself.

While the pair kept pushing for a government-sanctioned injection site, they weren’t waiting for official channels: VANDU ran several illegal sites in the DTES.

As VANDU members became more vocal, they attracted some unexpected supporters.

While speaking at a Vancouver Police Board meeting, Wilson met then-Vancouver Mayor Philip Owen and the two struck up an unexpected friendship.

Owen was a conservative politician from a tony part of Vancouver who wanted to know more about the crisis in his city. Wilson, a former salesman with a longtime addiction, could give him answers.

“We just formed this friendship, and it was very unlikely,” Wilson said. “I’ve got pictures of him downtown with me walking in the alleys, because he wanted to learn.”

Despite being elected with the right-leaning Non-Partisan Association (NPA), Owen embraced harm reduction, pushing for a four-pillars’ strategy in 1999 and crusading for the injection site.

Advertisement 7

Article content

He knew addiction wasn’t just ravaging the city’s poorest communities. At that time, though, few people in the middle class were willing to admit that publicly.

Parents group boosted support

Nichola and Ray Hall, along with their friends Susie and Rob Ruttan, who lived in the same manicured neighbourhood as Owen, decided to change that. Both couples had children who struggled with substance use, and both found it difficult to access treatment and long-term rehabilitation.

In 1999 they held support meetings for parents in a church basement and invited experts, including Osborn, to speak. He convinced the families that if they spoke publicly, people would listen.

It was scary to overcome the stigma, said Nichola Hall, but they created the group From Grief to Action, held public forums and spoke out about needing more services for drug-users. After some internal debate, they also endorsed Insite — a message that boosted public support.

“Philip Owen said it made a huge difference that we supported it,” said Hall, who at the time worked at UBC, where her husband was a professor.

Advertisement 8

Article content

Owen, who died in 2021, paid politically for supporting harm reduction. Although he was a popular mayor, the NPA ousted him as its leader.

The NPA then lost the 2002 election, which was won handily by former chief coroner Larry Campbell. The outspoken Campbell picked up Owen’s baton, and on election night promised to get Insite opened soon.

He went to Ottawa with a Vancouver delegation to speak with Health Canada, which eventually consented to a three-year pilot project as long as there was scientific research and protocols for overdose reversals and needle disposals. The facility also required an exemption from the federal Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, as well as financial and health backing from the province.

When Insite officially opened, the PHS’s Fader ran the place with two managers from Vancouver Coastal Health.

“I just remember in the first week, it immediately became clear how essential it was,” she said. “We were very quickly up to 1,000 visits a day.”

Visitors included those who had previously shot-up in isolated back alleys. Homeless people and those living in squalid SROs. Labourers, often self-medicating painful injuries. Office workers who stopped there in the morning before work and again on their way home. A couple who drove there every day from Surrey.

Advertisement 9

Article content

And 20 years ago, health-care workers didn’t have overdose-reversal tools like Naloxone, which have become common during the fentanyl crisis. Responding to the heroin overdoses was “intense and frightening,” Fader said.

“It was honestly hard to imagine it being worse when you were in those moments, and then here we are — it’s just so devastating. The number of deaths and the number of overdoses that our staff and community (now) respond to every day, every night is just something that I couldn’t have even imagined back then,” she said.

PHS expanded the site to include a detox centre and transitional housing for people waiting for long-term treatment.

“The experiment has proven successful”

But it would face more speed bumps. In 2006, Canada’s new prime minister, Stephen Harper, wanted Insite shut down. After a protracted legal battle by Insite’s backers, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled unanimously in 2011 that the federal exemption to drug laws should continue so the facility could remain open.

“The experiment has proven successful. Insite has saved lives and improved health. And it did those things without increasing the incidence of drug use and crime in the surrounding area,” Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin wrote.

Advertisement 10

Article content

Wilson, who attended the court hearing in Ottawa, phoned his mother to celebrate the legal victory and excitedly predicted these sites “would now be everywhere.”

The pace, though, has been slow. Insite remained the only federally sanctioned one in Canada until 2016, when the smaller Dr. Peter Centre near St. Paul’s Hospital was approved.

The federal government says there are now two other Ottawa-backed sites in B.C., Hope to Health in the DTES and one in Victoria. In addition, there are two dozen in Ontario, five in Alberta, four in Quebec and one in Saskatchewan.

Five other Canadian sites that have federal exemptions aren’t operating, and 11 more have applications to open.

But the status of these facilities tends to sway in political winds. Since the United Conservative Party came to power in Alberta in 2019, sites there have closed or plan to close. There has also been recent political opposition in Ottawa and Toronto.

Canada also has less-regulated overdose prevention sites, which tend to be peer-run, lower barrier operations that offer fewer services and can be opened more quickly because they don’t require federal approval, but typically need permission from the province.

Advertisement 11

Article content

(Health Canada issued exemptions to each province to allow them to open these “temporary” sites to respond to urgent needs.)

Vancouver Coastal Health and a non-profit opened one of these in Yaletown in 2021, but the City of Vancouver will not renew its lease after local businesses and residents complained it created significant disorder on the street.

The seed for these less-regulated facilities was planted in 2016, after B.C. declared the overdose epidemic a state of emergency, when Livingston helped Overdose Prevention Society co-founder Sarah Blyth-Gerszak open a site under a tent in the DTES.

It operated illegally for a few months before getting funding from Vancouver Coastal Health, and the provincial government opened 18 similar overdose prevention sites across the province.

Wilson, a peer facilitator at the B.C. Centre on Substance Use, said that led to similar sites opening in other parts of Canada, but lamented that it took so long after Insite. And he’s angry at the criticism against these facilities when there isn’t enough funding for treatment beds or detox, or sufficient access to safe, regulated drugs.

Advertisement 12

Article content

“We need harm reduction to keep people alive. And we need treatment once they’ve decided to make that step,” he said.

Outside Canada, supervised consumption sites have grown “substantially” and have started to open in the U.S., Kerr said.

The UBC professor finds it discouraging, though, that 20 years after he began collecting data at Insite, there are still skeptics.

“The stigma and discrimination associated with drug use just unfortunately leads the public to make all these unfounded and poorly supported arguments against these facilities,” he said.

One of his findings, Kerr said, was an increase in drug-users pursuing abstinence after Insite opened because they were connected to health-care workers there.

Critic question the success of safe injection sites when overdose deaths have increased alarmingly, and street disorder in the DTES has worsened.

Kerr argues the desperation on East Hastings is largely due to a major increase in poverty and homelessness, the toxicity of the drug supply and a lack of some harm-reduction options, such as smoking inhalation rooms.

Advertisement 13

Article content

“We don’t have a solid, evidence-based addiction treatment program to help serve people. And, in the case of overdose prevention sites and supervised injection sites, we really don’t have that many of them,” he said.

Related Stories

-

Five B.C. cities seek injection sites as overdose crisis continues

-

B.C. developer asks court to shut down Yaletown supervised injection site

Over the last two decades, Insite has filled gaps beyond overdose prevention, Fader said.

In an email, Vancouver Coastal Health said there have been nearly 1.7 million visits to Insite since 2004 for reasons other than a supervised injection, including immunizations, wound care, opiate agonist therapy and referrals to specialists, support to access housing, basic needs and medication, and connection to cultural services.

Fader insists vast societal improvements are needed — a more sufficient safer supply, the creation of inhalation rooms, improved housing — or the number of vulnerable people on the sidewalks outside the facility will continue to grow, in spite of the work being done inside.

Advertisement 14

Article content

“If we didn’t have Insite, there would be a lot more people using out on the street and there’ll be a lot more people dying in back alleys,” she said. “But, obviously, a lot more needs to be done and things have become even more dire.”

Hall, who has one son still struggling with drugs, is disappointed that more than two decades after starting From Grief to Action, there is still such a large addiction problem and a dearth of treatment, mental-health and prevention programs.

“We haven’t come far enough. It’s gotten worse and it seems like such an intractable problem” said Hall, a member of the B.C. Centre on Substance Use’s families committee.

Standing outside the supervised injection site she lobbied to open two decades ago, Livingston says she is now helping to establish overdose prevention sites in Nanaimo and Surrey, which are both facing opposition.

“I was in my 40s when I was doing all of the activism around getting Insite opened. Now I’m in my 60s,” she said. “To think that we just have to do it all over again. I’m not going to be down here in my 80s doing some other thing that I already did? I don’t want to plow the same field over-and-over again … It’s been tough.”

Advertisement 15

Article content

Some of the details in this story came from the book A Thousand Dreams: Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and the Fight for its Future, by Larry Campbell, Neil Boyd and Lori Culbert.

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the news you need to know — add VancouverSun.com and TheProvince.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.

You can also support our journalism by becoming a digital subscriber: For just $14 a month, you can get unlimited, ad-lite get unlimited, ad-lite access to The Vancouver Sun, The Province, National Post and 13 other Canadian news sites. Support us by subscribing today: The Vancouver Sun | The Province.

For more health news and content around diseases, conditions, wellness, healthy living, drugs, treatments and more, head to Healthing.ca – a member of the Postmedia Network.

Article content

Originally posted 2023-09-15 14:00:46.

Comments

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion and encourage all readers to share their views on our articles. Comments may take up to an hour for moderation before appearing on the site. We ask you to keep your comments relevant and respectful. We have enabled email notifications—you will now receive an email if you receive a reply to your comment, there is an update to a comment thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information and details on how to adjust your email settings.